The Mt. Kearsarge Indian Museum in Warner has been recognized as one of the top ten Native American Museums in the United States by PowWows.com, a website that celebrates Native American culture. Founded in 1990 by Bud and Nancy Thompson, the museum is celebrating its 34th season.

Andrew Bullock, museum director for the past six years and one of its first trustees, talks about the museum’s unique blend: “So, we have seven different galleries arranged geographically all over North America. A lot of people, they come here, assume we’ll have some Abenaki baskets from New Hampshire, so they are really surprised that we have such a diverse collection. The way the museum is arranged through the seven galleries, people can compare the clothing styles, the transportation, or housing styles between the different regions.

“The two things that I like to encourage people to come away with after they come to the museum is that native people are still here, alive and well in New Hampshire, even though the state of New Hampshire doesn’t recognize any native people. So that is one tenet that we want to impress upon people. And the other is that it is not one monolithic culture all across North America.”

He continued, “As far as artifacts, we have clothing, we have tools, we have examples of housing, basketry, pottery, and textiles. And again, we emphasize that, even to this day, but certainly traditionally, people were harvesting materials locally. So, if they’re going to make a basket, they need to know what plant to harvest, when to harvest it, and how to prepare it before they even make a basket.”

Beginning a tour of the museum, Andy comments, “We call this space the our Contemporary Art Gallery. This exhibit is called Baskets: Carriers of Life and Spirit, and we’ve got a combination of things, some contemporary baskets made by some native folks here in the Northeast, some baskets from our collection, and some of the tools that people need to make a basket.”

He points to an ash log. “A vast majority of the baskets in the Northeast are done using the ash log. We also have some sweet grass which is pretty integral to most of the Northeastern baskets. Some consider it medicinal and its aromatic qualities are remarkable.”

This year, the museum will offer a series of workshops in conjunction with the exhibit.

“One is going to feature Sherry Gould, who is a basket-maker, and she is going to demonstrate some of the techniques of making baskets,” he said. “We will also talk about how it is important to keep the tradition alive. And then we will have some other fun workshops, like a basket printing for kids. We are hoping to have a naturalist come and talk about the Emerald Ash Borer, which are decimating the ash trees. We want to have a kind of holistic conversation.”

Jennifer Lee, a contemporary basket-maker, led a workshop with 15 participants making baskets of ash bark. Andy states, “She just a wonderful resource because she can explain the technical part of baskets that talks about harvesting it.”

Exhibits in the front display case change periodically. Currently, the case contains a selection of Southwestern Kachina dolls, donated by Mike and Rita Griffin.

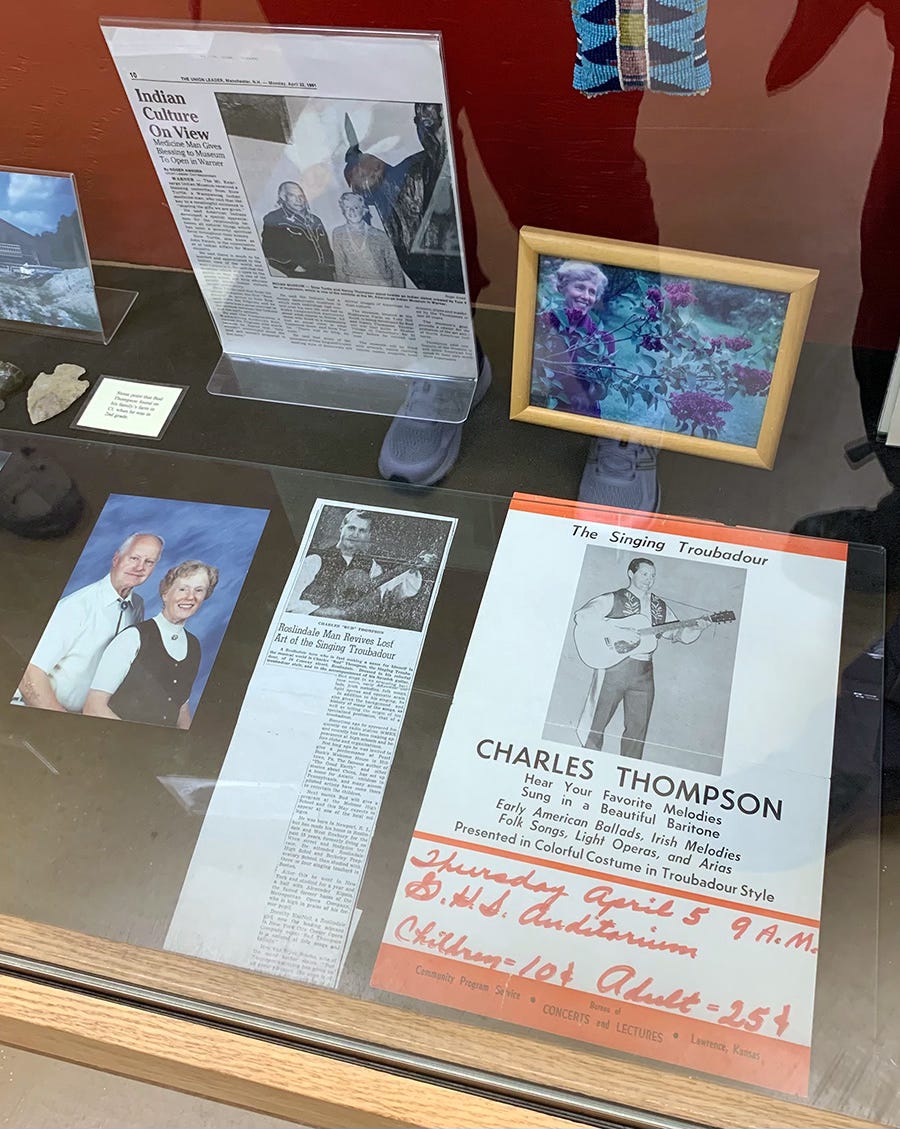

As we walk down the hallway, there is a display case dedicated to Bud Thompson, with a picture of Chief Sachem Silver Star; a dugout canoe made of white pine and a birch bark canoe, relics of New Hampshire’s first transportation highway — the water.

We are entering the Northeastern Gallery (New England, New York, and Maritime Canada.) To the right is an example of a wigwam made of logs and birch bark. Exhibit items include ash baskets, porcupine quill baskets, moose hair embroidery, and fancy beadwork, some created for the tourist trade. One of Bud’s favorite pieces was an enormous embroidered moose hair tablecloth or altar cloth, Andy notes.

“But remember, even the colonial homes in the 1700s and 1800s relied on these baskets to store their clothing and their food, at a time before Tupperware containers,” he said. “Then they became more fancy and more decorative.”

Andy then veers onto a different and important topic. “This is one of our segues into hard conversation, like boarding schools and residential schools and things like that. And people don’t realize that boarding schools went (some of them) until 1990. And so, it is important for us to talk about beautiful art and all that, but I think it is also incumbent on us to talk about boarding schools, missing and murdered indigenous women, Emerald Ash Borers, and the Trail of Tears.”

The Southeast Gallery has baskets made of river cane, pine needles, and honeysuckle vine; a stand-and-pole cypress canoe; examples of Seminole patchwork; a selection of Indian corn; a grinding stone; mortars and pestles; and a hoe made from an animal’s shoulder blade.

Andy says, “A lot of people don’t realize that corn started out as not much more than a glorified grass. But there are hundreds and hundreds of varieties of corn, even to the extent some of the corn had husks on each kernel, so you can imagine, to have a meal you really have a lot work ahead of you. But they were actually able to understand that sometimes the kernels would come out without a husk, and they would save and plant that seed next year.”

The Southwest Gallery showcases a mural of an Anastazi cliff dwelling. Andy comments that the Navajo came late to the Southwest and did not start making blankets until the Spanish introduced sheep. Later, the traders encouraged them to make rugs, not blankets, and then sold the rugs to the tourists who came on the Santa Fe Railroad.

Moving on to the pottery, he comments, “Again, making some generalizations, but this is done using the coil method. So, you take a rope of clay to make the shape you want, finish it with a smooth stone or another broken piece of pottery to get the shape. Fire it in a sheep dung fire rather than an electric kiln or something like that. And all the decoration is hand-painted. And again, they had to know where to get the clay and they have secret places where they get the good stuff.”

In addition to artifacts, contemporary artwork also is showcased.

“Here is contemporary artwork from the Southwest, so people realize that native artists are still doing wonderful things,” he said.

“A lot of people are familiar with Southwest turquoise jewelry. Pre-contact, they would maybe drill a hole in a turquoise nugget and make a necklace. Silver smithing didn’t really start until the Spanish came and taught some of those skills.”

A giant Apache basket called an olla was, according to Andy, another of Bud’s favorite pieces. Woven throughout the basket as a design element is a material called devil’s claw.

“This material is called devil’s claw, which is closer to cactus, so they can actually peel and weave it into the design, so you can see that it is both inside and out. So it is integral to the basket.”

The California Gallery is a small exhibit, but separate because of its distinctive and unique basketry, using such elements as red bud, maiden hair fern, willow, and devil’s claw.

Pointing to one, Andy says, “This basket here is quite a remarkable one. Those little feathers on the end are a quail’s topnotch and each quail has only one. So this one used lots of quail, probably for a prestigious gift basket.”

The Great Plains Gallery has everything, from a mounted buffalo head (at a height to illustrate the buffalo’s size) to a tipi and a horse pulling a travois.

Andy continues, “A lot of people are somewhat familiar with tipis, and buffalo or bison. And so we started the conversation here with pre-contact. Again generalizations, but a lot of people on the plains are at least semi-nomadic. So we have got to remember that they didn’t see one bison, you’d see 5,000 or 10 square miles of bison coming out here. But we talked about being semi-nomadic and getting virtually everything they need from the bison.”

He says, “Around 1850, they started to transition to canvas tipis. It’s a lot lighter. A buffalo tipi would probably require eight buffalo hides. Eight bison, sew them together and then you’ve got a cover that weights 300 pounds. So the practicality of canvas. There is a lot of engineering in a tipi. What we are looking at is the cover, which is rolled up so we can see inside. But, ordinarily, the cover would be down, and there would be about a six- or eight-inch space at the bottom. And if you look in the back, you can see an interior wall that goes about six feet up. That’s called the liner, and you’ll notice that it goes all the way down to the ground. What it does is create a natural draft so the air comes up between the walls and pulls the smoke out the top. Okay, so they’re quite ingenious, quite portable, and quite practical.”

He continues, “Once horses were introduced by the — again, mostly the Spaniards, but also other groups — it totally revolutionizes the plains environment. It was a lot easier to hunt a bison on horseback. A lot easier to haul a tipi. It really changes the dynamic of the plains. The exhibit of saddles really, I think, explains the diversity, creativity, and thought.”

Other displays include catlinite (tobacco) pipes with bead-embroidered pipe bags, bear claw necklaces, decorated blanket strips, and women’s beaded dresses.

Andy admits that his “main weakness is beadwork. I love the history of where the beads originally came from and how they’re made and have a great appreciation for the work going into them. Almost all of the glass seed beads that you see in the museum were made in Murano and Venice, Italy, and have been traded to North America.”

Andy indicates some signs saying, Adopt an Artifact. “We have this campaign once a year, and folks can adopt symbolically an artifact for the year and it’s a great way to support the museum.”

We end the tour with the Northwest Coast (including Alaska) Gallery with its baskets made of cedar bark, birch bark, and sea grasses, and soap stone carvings.

Andy points out, “Again, they’re using materials that they found locally. I’m always intrigued to see that little basket with the ivory finial on top made from baleen.”

Pointing out a woolly mammoth tooth, he comments, “So, and people say, ‘Why the heck do you have a woolly mammoth tooth?’ And to me it’s a natural fit. When we have third-graders to come study native people, they say, ‘It’s cool,’ or ‘gross’, or whatever it is. And then we can talk about the next group that comes through (Ph.D. candidates or whatever). So yeah, they are finding these things up there now because of global warming. All these things are washing out of riverbanks. So that’s out connection to the environment. And people, I think, understand it, when you put it in those terms.”

Reminiscing, Andy talks about a program where they partnered with the McAuliffe-Shepard Discovery Center in Concord to gaze at the night sky. “And at one point, this kid came up to me and said, ‘You know, I’ve never been outside in the dark.’ And to think, to think, that we could be part of that experience for kids. I think that is pretty amazing.”

The museum’s grounds have a Medicine Woods Walk and Arboretum with 75 species of trees, where one can explore and learn about Native uses of plants for food, medicine, and crafts.

The Harvest Moon Festival is planned for September. There will be a family day of nature presentations, hands-on crafts, and native foods.

The Beadstock event celebrates beads from around the world, with bead vendors, speakers, demonstrations, raffles, and more.

The Mt. Kearsarge Indian Museum, located at 18 Highlawn Road in Warner, is open May through October on Mondays through Saturdays from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. and on Sundays from noon to 4 p.m. Guided tours are offered at 10:30 a.m. and 1:30 p.m. most days, and Sundays at 1:30 p.m. only. For more information, visit www.indianmuseum.org.

Bud Thompson - Museum Founder

Museum Director Andrew Bullock tells the tale of the founder of the Mt. Kearsarge Indian Museum, Bud Thompson:

As a child, he grew up in Pawtucket RI and his grandfather had a farm. He was helping his grandfather at seven years old and coincidentally found an arrowhead. This inspired him on a lifelong journey to read everything he could about Native people, and so that was the impetus.

And then, I think, it was second grade, they had a visitor come to their school, which was a one-room schoolhouse kind of arrangement. And the person that came to the class was Chief Sachem Silver Star of the Paucatuck Eastern Pequot Nation. He credited that chance encounter with just setting him on this path that would ultimately lead to all kinds of wonderful things. So that really inspired him to become an avid reader and historian.

Skip forward 20 years and he was a troubadour, literally in the troubadour sense of singing folk songs, spiritual songs, all of that sort of thing on tours in the Midwest. And there was a push to discover unrecorded folk songs.

That is what brought Bud to investigate the utopian communities like the Quakers and Shakers. He knocked on the door [at the Shakers in Canterbury] to explain his interest, and I think, quite literally, they fell in love with each other’s mission and mindset, and he ended up ultimately living there for 30 years. And when he arrived, the property had already been put up for sale and was going to be developed. He helped them realize that there was so much potential there. He brought the Shaker sisters to Sturbridge Village, introduced them to the director of Sturbridge Village, who helped the Shakers understand that what they had in Canterbury was this intact community. So Bud helped them turn Shaker Village into a nonprofit cooperation and helped them to kind of develop this program to invite visitors.

This is when he really started amassing his Native American collection in earnest. His collection, I believe, was in the schoolhouse on the second floor. So when I would go and visit him as a youngster, we would climb this very steep staircase, which was probably closer to a ladder. And then, in the loft area of that building, were just boxes of wonderful collections of native material. And at that point, he’d say, “You know, Andy, this is going to be the Plains Indian collection,” and “Andy, this is going to be the horse collection.” You know, as a quite a bit younger guy, I thought, this guy is nuts. Nothing is ever going to come of this.

So again, fast forward to 1989, I guess. I was up visiting him and he threw me in the van and we came to Warner, pulled into the driveway up at the corner, and came into, at that point, an abandoned riding arena. So there was literally wood chips on the floor and pigeons in the rafters. His vision was to turn the [place] into a museum with a voice. So it was never going to be the biggest pottery collection or the rarest. His vision was around making it accessible and being able to educate the public through the collection. We have 12 acres of land here. And he was quite adamant that it is important for people to come and have a chance to walk outside and see a birch tree growing and then come into the museum and see a canoe that is made out of birch bark, or a moose call. So he didn’t really differentiate between artifacts and the natural environment.

Initially, the museum was the private collection of Bud and Nancy Thompson for the first few years, and they ended up donating it to the non-profit cooperation.

Bud passed away almost three years ago at the age of 99-years-old. So, he was here two or three days a week to really keep us on the straight and narrow.